The Moneyball opportunity in basketball

Published

Aren't we over all this analytics crap yet? All those damned numbers and charts and tables and the biggest impact the "analytics movement" had was proving Steph Curry right—a 3-pointer is worth more than a 2-pointer.

The Moneyball opportunity in basketball is different.

I don't care about starting a movement. I'm not interested in optimizing the game into some boring, predictable thing. I want my team to win. I want them to win it all. 🏆 I want the people who run my team to think like tech founders—use deep intuition to make bold moves, not follow the herd.

If my team can gain a massive edge against competition, I want them to exploit the hell out of it. And I don't want them to invite Michael Lewis over to write a book when they do.

It's a truism in tech that founders of successful companies get replaced by the bean counters and the optimizers. Intuition and bold moves get replaced by the diminishing returns from decision by spreadsheet. Too much abstraction, too little feel for the game. And that is used as an excuse to ignore numbers and rely on the eye test.

But here is a trick with basketball—there is still a massive founder-like edge for a team to grab and the right numbers are a critical way to see it. How do I know? Listen to one of the sport's founders, Howard Hobson. Coach of the first NCAA champs in 1939, innovator of the shot clock, goaltending, the "home run of basketball" (the three-pointer), and much more.

Not only did Hobson implement most of the core rules that transformed James Naismith's YMCA winter sport into the modern game we know, he applied his insight to winning games for his teams, and then he wrote a book complaining about how fans and pundits don't get it. Hobson is one of basketball's true founders. He wanted fans to see the game with the same appreciation for winning that he could. (How democratic of him.)

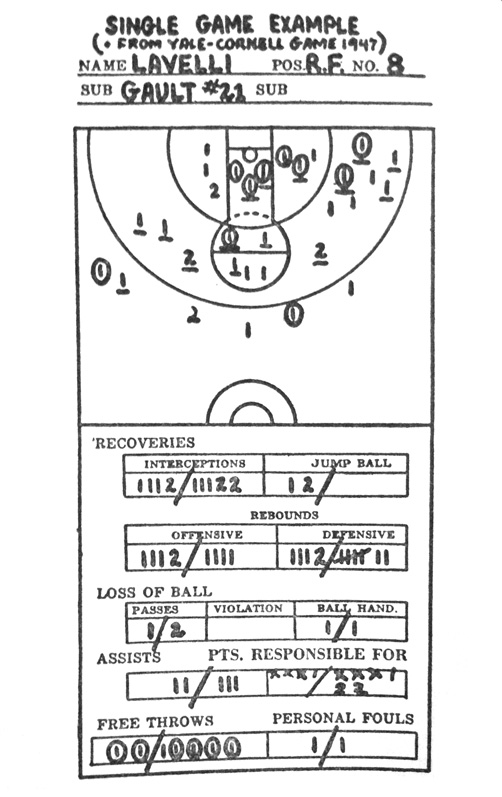

Crucially, he didn't believe he could just stare harder than the next guy at such a fast-paced game to see what separated winners from losers, so he applied the scientific method to measuring important events, especially ones related to possession of the ball and shooting efficiency, then visualized them in new ways. Take his single-game player sheet. Note what it emphasizes, as well as what it doesn't (points).

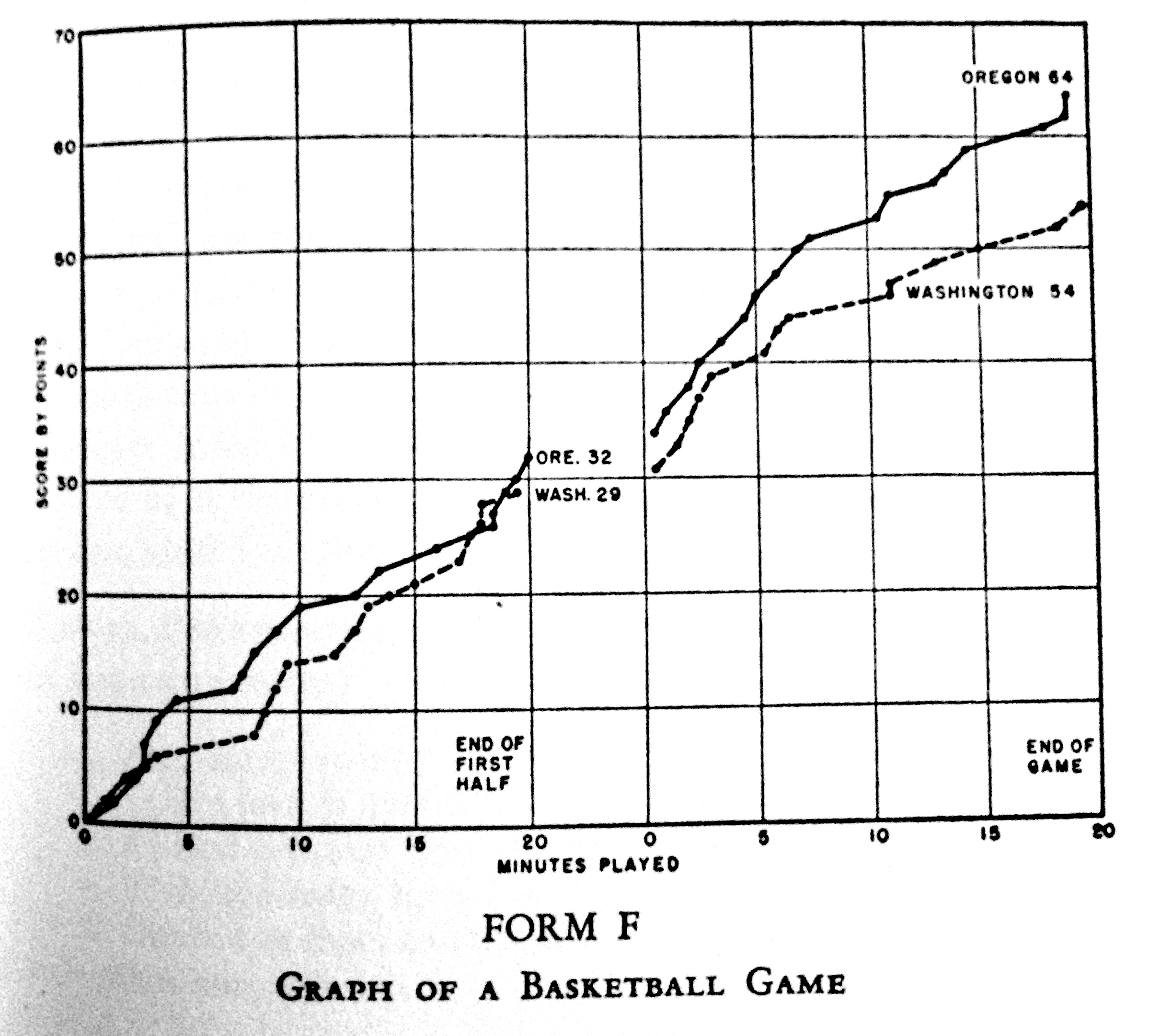

Or look at how he focused on the ebb and flow of slim leads and deficits by introducing a game flow chart.

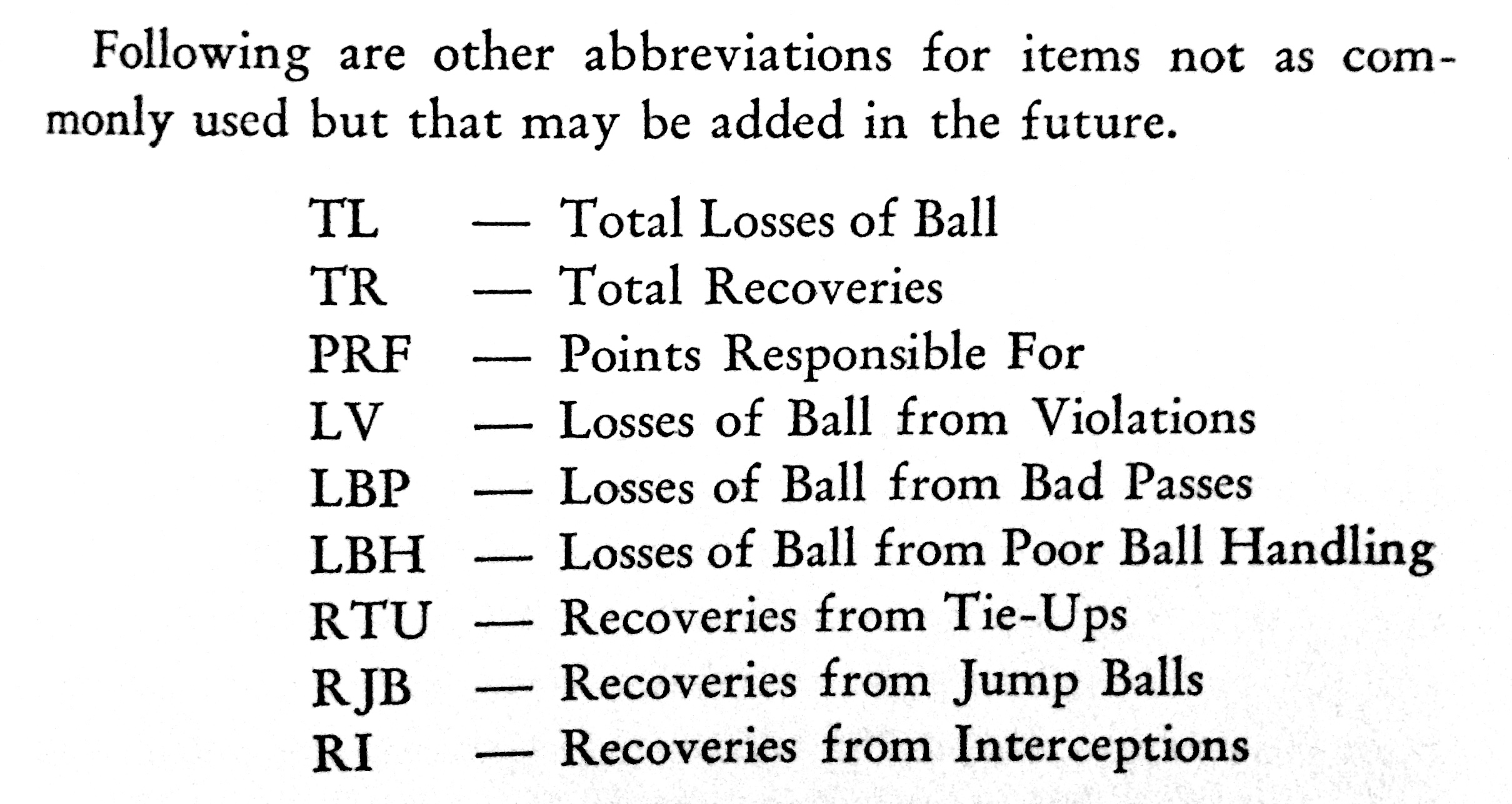

Hobson cared so much about possession of the ball, he even tracked six way a player can change possession without a shot!

Reading Hobson today, you realize we crib his charts but not his insight. He'd still be complaining about the fans and front offices. We've complicated the game with "advanced analytics," but we haven't learned his simple lessons about what makes the game tick. Take this excerpt:

In a crucial Madison Square Garden game that will never be forgotten, Oregon led Long Island by a 15-point margin at the start of the second half. Long Island had several great “ball hawks” and their timely interceptions resulted in goals that cut down the Oregon lead. With ten seconds to play, Oregon still held a two-point lead. Out of nowhere came a “ball hawk” who intercepted a pass and fed the ball to a teammate who tied the score. Long Island went on to win in overtime 56-55. Who received the credit?--the player who scored the basket. The interception was soon forgotten.

Hobson's founder intuition is like the "Moneyball" opportunity Billy Beane and Paul DePodesta exploited for the Oakland A's benefit in baseball. It reveals "the epidemic failure within the game to understand what is really happening [leading people who] run major league baseball teams to misjudge their players and mismanage their teams." The A's cracked it, then made the mistake of drawing too much attention to their edge, inviting competition.

In basketball, no team has done anything close. Instead of Moneyball, we got Moreyball (3 > 2 points) and an avalanche of unscientific spreadsheets, vanity metrics, cherrypicked stats, and pretty charts by people jockeying for front office jobs. (I know, I got caught up in it.) It didn't move the needle on the game or, more importantly, for my team.

One founder-like person (an economist like DePodesta!) did reproduce Hobson's core insights in the 2000s. He scienced the shit out of basketball, only he didn't take a front office job, he wrote a book about it first. Like Hobson, he wanted fans to appreciate the game more fairly. Trouble is, these insights go against conventional wisdom. Normal people don't like that, which is why it takes a founder to have the guts to decide against the grain.

One team could exploit the heck out of this. I hope it's mine.